Slop

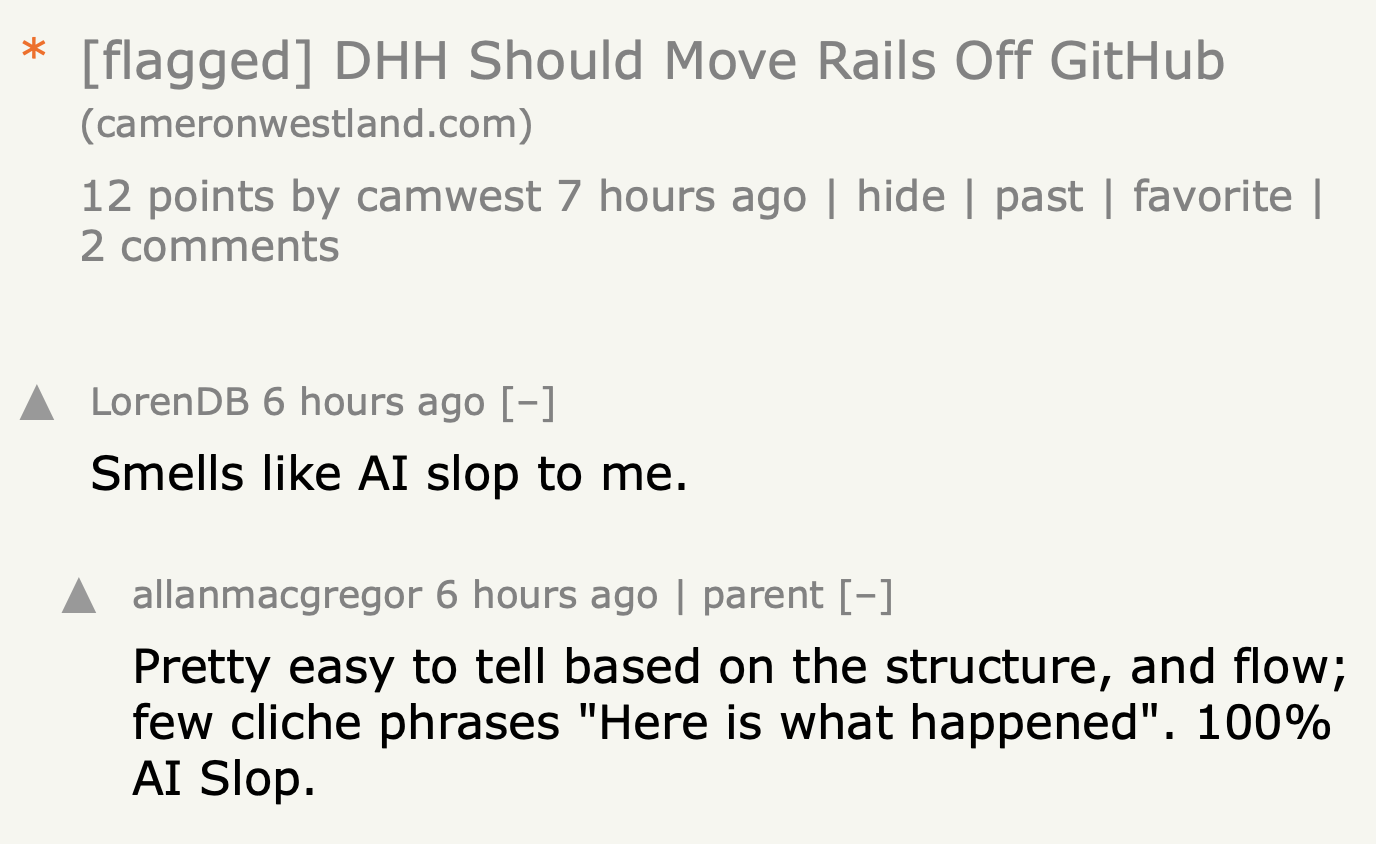

My post about DHH moving Rails off GitHub got flagged on Hacker News within an hour:

They’re not wrong. I did use AI—for transcription, for structural editing, for finding holes in my argument. But every claim was mine. Every link was verified by me. I spent hours on it.

The problem wasn’t that I used AI. The problem was that engagement-optimized writing now looks like AI slop.

What the Dickie Bush Playbook Became

I learned to write online from Dickie Bush. His approach worked: punchy hooks, clear structure, “here’s what happened” → “here’s the insight” → call to action. It respected the reader’s time and made ideas scannable.

That playbook is now what AI-generated content looks like. Not because Dickie was wrong—his advice was good. But LLMs trained on successful online writing learned exactly those patterns. When you stack a TL;DR, a hook, “here’s what happened,” and a dramatic reveal, you trip pattern matchers. The structure that once signaled “this person knows how to write online” now signals “this was probably generated.”

Why I Still Use AI

I write more when AI handles the friction. Right now I’m walking to the gym, dictating this into my phone. If I had to transcribe and edit it myself, I wouldn’t do it.

This is what AI works with. The ideas are mine; the cleanup is collaborative.

In 2006, I won a Mac developer competition called My Dream App. Steve Wozniak was one of the judges. I was 23. Part of the competition required posting updates—progress reports, vision documents. I wrote one of those updates the way I’d been writing on IRC for years: stream of consciousness, hit enter every few words. First comment: “Why is there such terrible punctuation, terrible writing…”

I was enthusiastic, then insanely deflated. I went back and fixed every typo so people would engage with my idea instead of my formatting. To me, that problem is now solved.

The Risk Is Misrepresentation

The problem isn’t AI assistance. The problem is when AI generates things it can’t know.

AI can’t get in my brain. It doesn’t know what I observed, what would change my mind, what I’m uncertain about. When it fills those gaps, it’s not helping me—it’s misrepresenting me.

I rewrote my style guide around one idea: Claude is an editor, not a co-author. Editors shape raw material. They cut, compress, interview you for more when it’s thin—but they don’t invent. If a claim is missing, Claude asks. It doesn’t generate something plausible.

Simon Willison wrote yesterday that when you use AI for code, “your job is to deliver code you have proven to work.” Same here: your job is to deliver writing you have proven to own.

The Uncomfortable Part

I don’t know if this solves the problem.

This post was developed in a Claude Code session. If I shared that session log, you could verify I was steering—that claims came from me, that I rejected auto-generated counterarguments for my actual uncertainties. Are we heading toward a world where the session log becomes “view source” for writing? That seems insane. But maybe?

AI will get better at avoiding these tells. Whatever signals work today—artifacts, primary links, visible uncertainty—will be what LLMs produce by default tomorrow. Merriam-Webster made “slop” the word of the year. The arms race doesn’t end.

All I can do is be transparent about my process and stake my reputation on my claims. Whether that’s enough—I don’t know.

Process note: This post was drafted from voice memos and developed in conversation with Claude Code. AI was used for research, transcription, and structural editing. All claims and opinions are mine; mistakes are mine.